Choices: Exercises or Music, Trumpeter or Musician, Bricks or Cathedral

A recent message I sent to my students:

We need to take time to think carefully about several things that have a relationship to trumpet.

We live in a time where almost everything is instantaneous and easy:

•information—the internet

•food—UberEats

•transportation—Uber/Lyft.

I fear that our perspectives regarding trumpet and skill development are practically the same... one "secret" or one specific physical change, and everything will finally "work."

What are your goals with the trumpet?

More basic, what is the trumpet?

Does the trumpet function as an extension of your musical ideas or does it function simply as a tool to produce various sounds/effects? It is an important question because the answer will determine how you will approach work...musical thoughts or mechanical thoughts? Playing exercises as goals or having goals for playing music?

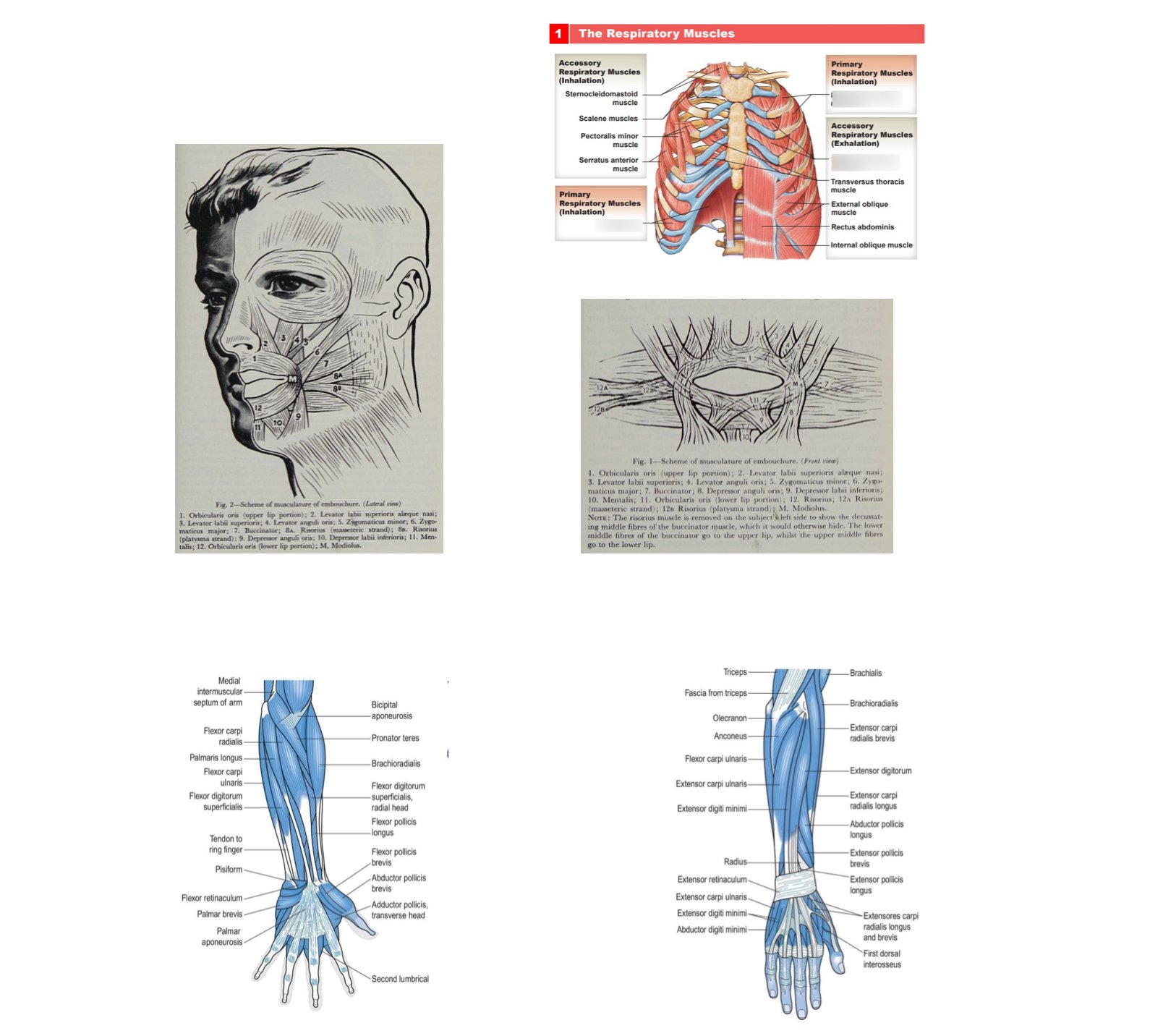

Skill development is a process of overcoming difficulties of a passage unplayable at a given moment. Remarkably, our muscles don't know the difference between Clarke No. 2 or a passage from Jolivet...the movements are simply actions...one direction, each muscle. The brain has the ability to simultaneously control the respiratory system (diaphragm, lungs, muscles), the fingering/dexterity system (fingers, hand, arm), the face (corners, jaw, chin, lips), simply because of an image/idea we have...a sound, vowel, consonant, phrase, articulation, piano, forte, brilliance, crescendo, diminuendo, pulse, etc...

"Deep Practice"

"Deep Practice" is the intense work in which we are so focused that we can make minute adjustments based on our musical instinct... a more refined sound, faster fingering, smoother and more precise articulation, being relaxed so that intense dynamics are not forced. This is natural... this is technical evolution based on musical intuition. It is not based on a formula or a diagram; it is based on trial and error with musical objectives. This intense work is not possible without advanced musical ideas and concepts.

Be patient, listen, trust your progress... base your adjustments on sound, ease, precision, and musicality.

Imagine shooting a basketball during a basketball game, focusing only on the muscle in the last joint of your little finger while simultaneously running down the court with a defender running next to you...does that make sense? Do you think you will be successful?

Why would you think this approach would work on the trumpet?

Of course, during team practices and/or individual work, we need to focus on shooting or dribbling control (or high notes or flexibility), but even when focusing on these specific aspects, we are still working muscle groups (coordination), not individual muscles. And, ultimately, dribbling alone doesn't make a basketball player (or musician).

The idea that we can consciously focus on one individual muscle or another individual muscle while we're talking about muscle systems/groups that function unconsciously, in combination, won't work because the brain, nerves, and muscles simply don't work in that manner. We need to have an image/idea: of the sound, phrase, clarity, articulation (basically, music) that we want, and then the process/work is using the correspondence between that "SONG" (sound/musical aspects) and engaging the "wind" (breath/muscle technique). The unconscious mind works faster (more efficiently) than the conscious mind.

Often, when we introduce conscious methods/actions into unconscious processes, the result is hesitations/blockages of natural processes (inability to release air…start a note). Yes, we always need to make small adjustments (vibration points, attention to general physical aspects, coordination between systems) to overcome difficulties and to evolve, but these adjustments need to be based on goals, musical decisions, and musical needs.

(Complexity of systems: control of individual muscles…conscious or unconscious? Visual adjustments or adjustments based on sound/musical ideas? When we walk, run, jump, talk, sing, do we think about each muscle?)

Is it possible to perform Beethoven's 5th Symphony or Bizet's Carmen just by working on Clarke 2 in low G major? Perhaps a better question would be why choose an exercise (Clarke 2), when we have so many additional materials/resources with better musical/technical connections to Beethoven and Bizet and their musical needs. We can expand on this example: Alpine Symphony only working on Stamp... Scheherazade with only Arban... does that make sense?

Instead, imagine (for Beethoven and Bizet) a "diet" of recordings, Bousquet, Snedecor (studies in the low register), Sachse with transposition, 2nd trumpet excerpts (Brahms, Mahler, etc.)... musical situations involving register, articulation combinations, slurs, dynamics, phrasing, etc. Which approach (exercises or music or a combination) will use/activate the mind, technique, and an environment most similar to that of an orchestra? Which approach will allow for better overall development? Which approach will encompass trumpet, music, and creativity?

At the end of the day, if you want to play music professionally but you are not practicing/playing actual music, what do you think the result will be? When we play a passage four times incorrectly, then once correctly, and then try to move on to the next passage, what is being reinforced...what is “imprinted” in our muscles?

If 90% of practice consists of rudimentary exercises and 10% music, what will be “imprinted” in your brain and muscles...what are you developing, what are you working on, what are the goals?

Again, does the trumpet function as an extension of your musical ideas, or is it simply a tool for producing various sounds/effects?

Three phrases that I (unfortunately) think relate to us are:

•"The tail wagging the dog"

•"Put the cart before the horse"

•"Can't see the forest for the trees"

Having a musical approach does not mean ignoring problems or not using pedagogical tools; in fact it means using the correct and most efficient tools (brain/images) in coordination with correct perspective to obtain the best results.

Nothing on the trumpet (or any other musical instrument) happens overnight.

There are no tricks, no secrets; almost everything we do on the trumpet today was written hundreds of years ago (Altenburg, Arban, Clarke). However, what has changed is our understanding of how the brain works, how we learn, and how we acquire skills. Musical evolution and development on an instrument requires physical coordination acquired through musical determinations that travel from the brain to the nerves to the muscles.

When you speak, do you think about the position of your tongue or your throat? When we play the trumpet, vowels like a, e, i, o, u automatically alter the position of the tongue, the position of the lips, the position of the corners, and the position of the chin. Consonants like t, d, g, and k automatically change the character of our articulations without analyzing the tongue. "Words" like "ha," "ah," "who," and "hoo" automatically change tensions in the muscle groups of our thoracic/abdominal region. "Poo," "Emm," or "Mmmm" change the preparation/structure of our aperture without focusing on positions/placement of our lips.

All these complex physical/systematic adjustments occur using musical, vocal, and speech methods that already exist in our minds. Why wouldn't we use and expand on these elements? If our brain has the music, the sounds, the ideas, the concepts, it knows which electrical signals to send through the nerves to our muscles. "Deep Practice" is how we coordinate and adjust these signals/movements. It all starts with sound.

__________________________________

"You can have a lot of technique, but if you don't have tone/sound, you won't be attractive to the listener. First, it's hearing in your head; the other important part is your heart—having that innate part of our soul that needs to express itself. Music isn't just the black dots on white paper—it's what happens when those black dots on white paper enter your heart and come out again." —Phil Smith

—————————————————

"I feel there's a unique way I teach that's quite different from other teachers. I've worked on this as my specialty. It's not that I talk about things that aren't known or understood. Everything I say has already been discovered.

However, what I discovered was a way to structure it so that in your presentation there's a logical direction. It's also knowing that when you hear something wrong with your sound, you should pay attention because it's telling you something.

Avoiding just saying, 'I like it or I don't.' It goes deeper than that. Saying first, 'Okay, do you understand this? Are you ready to accept the sound and the limitations that come with it?' I would try any inductive way to stimulate thought. New thinking.

Then we trust that your body will try to convey the message to achieve this new concept. If it doesn't work, we try to go in the other direction. I never intend to change someone's playing from a physiological standpoint. I like to initiate musical imagination first, so that the person isn't left wondering which muscle is doing what.

If you don't supplement your daily maintenance with more interesting musical materials/resources, you are actually stifling growth. A person could develop wonderful muscular abilities, but they wouldn't be connected to what one should do as a musician. - Vincent Cichowicz

———————————————-

The story of the three bricklayers is a parable based on a true story. In 1666, after the great fire that devastated London, the world's most famous architect, Christopher Wren, was commissioned to rebuild St. Paul's Cathedral.

One day in 1671, Christopher Wren observed three bricklayers on a scaffold:

•One crouched,

•The other half-standing,

•And the third standing.

Christopher Wren asked each bricklayer a question: "What are you doing?"

•The first bricklayer replied, "I am a bricklayer. I work hard laying bricks to support my family."

•The second bricklayer replied, "I am a builder. I am building a wall."

•But the third bricklayer, the most productive of the three, when asked "What are you doing?" replied with a twinkle in his eye: "I am a cathedral builder. I am building a great cathedral for Worship."

—————————-

The question is…which one are you?

___________________

Coyle, Daniel. The Talent Code. Arrow Books, 2009.

Csikszentmilhalyi, Mihaly. Flow The Psychology of Optimal Experience. HarperCollins, 1990.

Gentian, Molly. Learn Faster, Perform Better: A Musician's Guide to the Neuroscience of Practicing. Oxford University Press, 2024.

Gray, Robb. How We Learn to Move: A Revolution in the Way We Coach & Practice Sports Skills. Perception Action Consulting & Education LLC, 2021.

Lemov, Doug. Practice Perfect 42 Rules for Getting Better at Getting Better. Jossey-Bass, 2012.

Parncutt, Richard and Gary E. McPherson. The Science and Psychology of Musical Performance. Oxford University Press, 2002.

Steenstrup, Kristian. Deep Practice Peak Performance The Science of Musical Learning. The Royal Academy of Music, Aarthus, 2023.

_________________________________

Uma mensagem recente que enviei aos meus aluno/as.

Precisamos tirar tempo para pensar bem sobre várias coisas que têm uma relação com o trompete.

Vivemos numa época em que quase tudo é instantâneo e fácil:

•informação-Google

•comida-Glovo

•transportes-Uber.

Receio que a nossa perspectiva em relação ao trompete e ao desenvolvimento de competências seja praticamente a mesma... um segredo ou uma mudança física e tudo finalmente "funcionará."

Quais são os vossos objectivos com o trompete?

Mais básico, o que é o trompete?

O trompete funciona como uma extensão das vossas ideias musicais ou é simplesmente uma ferramenta para produzir vários sons/efeitos? É uma pergunta importante porque a resposta vai determinar como vão trabalhar…pensamentos de música ou pensamentos das ferramentas?

Tocar exercícios como objectivos ou objectivos para tocar música?

O desenvolvimento das habilidades requer um processo para ultrapassar as dificuldades de passagens que não conseguimos tocar em determinado momento… os nossos músculos não sabem a diferença entre o n° 2 de Clarke ou uma passagem no Jolivet…são simplesmente ações…uma direção só, cada músculo. O cérebro tem a capacidade de controlar simultaneamente o sistema respiratório (diafragma, pulmões, músculos), o sistema de dedilhação (dedos, mão, braço), a face (cantos, mandíbula, queixo, lábios), simplesmente devido a uma imagem que temos…um som, vogal, consoante, frase, articulação, piano, forte, brilho, crescendo, diminuendo, pulsação, etc…

"Deep Practice"

“Deep Practice” é o episódio/processo de trabalho em que tão concentrados que fazemos ajustes minuciosos com base no instinto musical... um som mais refinado, uma dedilhação mais rápida, uma articulação mais suave e precisa, relaxada para que se forcem as dinâmicas intensas. Isso é natural... essa é uma evolução baseada na intuição musical. Não se baseia numa fórmula ou imagem; baseia-se na tentativa e erro. Isto nunca funcionará sem ideias e conceitos musicais avançados. Sê paciente, ouve, confia na tua evolução... baseia as tuas decisões no som, na facilidade, na precisão, e na musicalidade.

Imagina lançar uma bola no cesto durante um jogo de basquetebol só com foco no músculo na última articulação do dedo mindinho no mesmo tempo que estás a correr no campo com uma pessoa de defesa ao lado, contra ti…faz sentido?…pensas que vais ter sucesso?

Porque pensas que esta abordagem funciona no trompete?

Claro, durante um treino geral ou trabalho individual, precisamos focar só em lançamentos ou só no controlo de driblar (ou notas agudas ou flexibilidade) mas mesmo ao focar nestes aspectos específicos ainda estamos a trabalhar grupos musculares (coordenações), e não músculos individuais. E, no final do dia a capacidade só para driblar não resulta num jogador de basquetebol (ou músico).

A ideia de que podemos focar conscientemente num músculo individual ou outro músculo individual enquanto estamos a falar sobre sistemas/grupos musculares que precisam de funcionar inconscientemente em combinação, não irá funcionar, porque simplesmente o cérebro, os nervos, e os músculos não funcionam desta maneira. Precisamos ter uma imagem/ideia: do som, frase, claridade, articulação (basicamente música) que queremos e depois isso, o trabalho é para utilizar a correspondência entre o "SONG" (canção/musicalidade) e o "wind" (sopro/técnica dos músculos). A mente inconsciente funciona com mais velocidade (eficiência) do que a mente consciente. Demasiadas vezes quando introduzimos métodos/ações conscientes dentro dos processos inconscientes, o resultado é hesitações/bloqueios dos processos naturais. Sim, precisamos sempre de fazer pequenos ajustes (pontos de vibração, atenção em aspetos físicos gerais, coordenações entre os sistemas) para ultrapassar dificuldades e para evoluir, mas estes ajustes precisam de estar baseados em objetivos, decisões, e necessidades musicais.

Acham que podem tocar a 5a Sinfonia de Beethoven ou Carmen de Bizet só por causa do trabalho com Clarke 2 em Sol grave? Talvez a melhor pergunta seria porquê escolher apenas um exercício (Clarke 2) especialmente quando temos tantos materiais/recursos adicionais com melhor ligações musicais/técnicas com Beethoven e Bizet e as suas necessidades musicais. Podemos expandir este exemplo: Sinfonia Alpina só com trabalho de Stamp…Scheherazade só com Arban…faz sentido?

Imagina em vez disso (para Beethoven e Bizet), uma "dieta" de gravações, Bousquet, Snedecor (estudos no registo grave), Sachse com transposição, excertos de 2° trompete (Brahms, Mahler, etc.) …situações musicais que envolvem combinações de articulação, ligaduras, dinâmicas, frases, etc. Qual abordagem (exercícios ou música ou uma combinação) vai utilizar/activar a mente, a técnica, e um ambiente mais parecido com o da orquestra? Qual abordagem vai permitir uma melhor evolução geral? Qual abordagem vai abranger trompete, música, e criatividade?

No final do dia, se queres tocar música como profissão mas não estás a estudar/tocar música, o que achas que será o resultado? Quando tocamos uma passagem quatro vezes de forma errada, depois uma vez corretamente e passamos para a seguinte, o que está a ser reforçado... o que é que os nossos músculos se lembram mais? Se 90% do teu estudo é composto por exercícios rudimentares e 10% por música, o que é que o nosso cérebro e os nossos músculos se lembram... o que estamos a desenvolver, em que estamos a trabalhar, quais são os objetivos? Mais uma vez: o trompete… funciona como uma extensão das vossas ideias musicais ou é simplesmente uma ferramenta para produzir vários sons/efeitos?

A língua Portuguesa tem muitas expressões/ditados, "farinha do mesmo saco" …"são muitos anos a virar frangos"…a língua inglesa tem também. Três frases que penso (infelizmente) que se associam a nós são:

•"The tail wagging the dog"…literalmente, "o rabo abanando o cão"…ou, "uma parte pequena ou sem importância de algo está a tornar-se demasiado importante e está a controlar tudo."

•"Put the cart before the horse"…literalmente, "colocar a carroça à frente dos bois"…ou, "fazer as coisas pela ordem errada ou não natural, ou priorizar algo inconsequente em detrimento de algo mais essencial."

•"Can’t see the forest for the trees"…literalmente, "não consigo ver a floresta pelas árvores"…ou, "tão absorvido em pequenos detalhes ou aspetos particulares de uma situação que não consegue compreender o quadro geral ou compreender a situação na sua totalidade... uma falta de perspetiva devido ao foco excessivo em elementos individuais, impedindo uma visão abrangente do todo."

Isto não significa ignorar problemas ou não utilizar ferramentas pedagógicas, na verdade significa utilizar as ferramentas corretas e eficientes (cérebro/imagens) com a perspetiva correta para obter os melhores resultados.

Nada no trompete (ou em qualquer outro instrumento musical) acontece de um dia para o outro. Não há truques, nem segredos; quase tudo o que fazemos hoje no trompete foi escrito há centenas de anos (Altenburg, Arban, Clarke). No entanto, o que mudou foi a nossa compreensão de como funciona o cérebro, como aprendemos e como adquirimos capacidades. A evolução e o desenvolvimento musical num instrumento exigem coordenações físicas adquiridas através de determinações musicais que vão desde o cérebro aos nervos e aos músculos. Quando falas, pensas na posição da língua ou na tua garganta? Quando tocamos trompete, vogais como a, e, i, o, u alteram automaticamente a posição da língua, a posição dos lábios, a posição dos cantos e a posição do queixo. Consoantes como t, d, g, k alteram automaticamente o carácter das articulações sem análises da língua. "Palavras" como Ha, who, hoo, alteram automaticamente os grupos musculares da nossa região torácica/abdominal. "Poo," "Emm," ou "Mmmm," alteram a preparação/estrutura da nossa apertura sem pensar nos lábios. Todos estes ajustes físicos/sistemáticos complexos, ocorrem utilizando métodos musicais, vocais e de fala que já existem nas nossas mentes. Porque não usaríamos e expandiríamos esses elementos? Se o nosso cérebro tem a música, os sons, as ideias, os conceitos, sabe que sinais elétricos enviar através dos nervos para os músculos. “Deep Practice” é a forma como coordenamos e ajustamos esses sinais/movimentos. Tudo começa com o som.

—————————————————

“Podes ter muita técnica, mas se não tiver tom/som, não serás atraente para quem estiver a ouvir. Primeiro, é ouvir na tua cabeça; a outra parte importante é o teu coração — ter esta parte inata da nossa alma que precisa de se expressar. A música não são apenas os pontos pretos no papel branco — é o que acontece quando estes pontos pretos no papel branco entram no teu coração e voltam a sair.” — Phil Smith

—————————————————

"Sinto que há uma maneira única na forma como ensino que é bastante diferente dos outros professores. Trabalhei nisso como a minha especialidade. Não é que falo sobre coisas que não sejam conhecidas ou compreendidas. Tudo o que digo já foi descoberto. No entanto, o que descobri foi uma maneira de estruturá-lo de forma a que na sua apresentação haja uma direção lógica.

É também saber que quando ouves algo errado no teu som, deves prestar atenção porque ele está a dizer-te algo.

Evitar dizer apenas 'Gosto ou não gosto.’ É mais profundo do que isso. Dizer antes: 'Ok, entendes isto? Estás pronto para aceitar o som e as limitações que o acompanham?'

Eu tentaria qualquer forma indutiva para estimular o pensamento. Novo pensamento. Depois confiamos que o teu corpo tentará transmitir a mensagem para alcançar esse novo conceito. Se não funcionar, tentamos ir noutra direção. Nunca pretendo mudar a forma de tocar de alguém do ponto de vista fisiológico. Eu gosto de iniciar a imaginação musical primeiro, para que a pessoa não fique a pensar que músculo está a fazer o quê."

Se não complementares a tua manutenção diária com materiais/recursos musicais mais interessantes, estarás realmente a sufocar o crescimento. Uma pessoa poderia desenvolver habilidades musculares maravilhosas, mas estas não teriam ligação com o que se deve fazer enquanto músico." - Vincent Cichowicz

———————————————-

A história dos três pedreiros é uma parábola baseada na história autêntica. Em 1666, após o grande incêndio que arrasou Londres, o arquiteto mais famoso do mundo, Christopher Wren, foi encarregado de reconstruir a Catedral de Saint Paul.

Um dia, em 1671, Christopher Wren observou três pedreiros num andaime:

•Um agachado,

•O outro meio em pé,

•E o terceiro de pé.

Christopher Wren fez uma pergunta a cada pedreiro: "O que está a fazer?"

•O primeiro pedreiro respondeu: "Sou pedreiro. Trabalho arduamente a assentar tijolos para sustentar a minha família."

•O segundo pedreiro respondeu: "Sou construtor. Estou a construir um muro."

•Mas o terceiro pedreiro, o mais produtivo dos três, quando lhe perguntaram "O que estás a fazer?" respondeu com um brilho nos olhos: "Sou construtor de catedrais. Estou a construir uma grande catedral Para Deus."

—————————-

A questão é…qual és tu?